The Land of Enchantment/ Land of Entrapment

On land spirits, telling stories out of order, and why I can't set foot in New Mexico

At this point it has been almost three years since I crossed the state line into New Mexico.

For most of this time, I couldn’t think of the place without my stomach twisting. Couldn’t look at a map of the state, or at the luminous pink-orange mesas that still show up in my social media feeds.

If I crossed the state line, I was convinced, I would shortly cease to exist.

“There is a Being that wants me dead there,” I would say carefully whenever someone asked me why I didn’t pick a driving route through the state, or noticed my lack of enthusiasm at the mention of Ojo Caliente. (Please picture their facial expressions.)

I wasn’t sure of the mechanics, though. Would a car crash in Raton count? Could I disappear near Deming?

Or did I need to come within—was it one hundred? fifty? five?—miles of the mesa where, over the course of two and a half years, a malevolent entity slowly destroyed my life?

The problem with spiritual storytelling is: The arcs are long.

So far in this Substack I have walked you, in somewhat chronological fashion, from the death initiations that plunged me into my body, through the healing work that sharpened my intuition, into my first encounters with the spirit world. All of this gets us, more or less, to the day in early 2020 when I said yes to moving into a house on Glorieta Mesa, 15 miles outside Santa Fe.

But from here, things fall apart. Because it will look, at first, like a sort of homecoming. A glowy, unexpected-new-chapter, New-Mexico-looks-good-on-you kind of thing. It will look that way for quite a while.

And it’s not. Not really.

If I charge into this story without revealing its ending, much of it will feel like a Big Fat Nothing. We need the stakes to feel the tension.

And this is how spiritual storytelling works. What feels random taken alone can reveal itself to be the most striking end of a tale. It might be the piece on which everything hinges.

This story can’t move forward without me telling you about the Thing in my house.

Maybe you’re smarter than I was. Maybe you would have seen, as it unfolded, what was happening to me. (Sometimes I pull up pictures of myself from those years to stare into my own dark eyes. To sight what glinted there.)

Or maybe, like me, the breadcrumbs would have seemed to you like nothing—then like chaos—until they stopped your breath with order.

Where I’m from, we don’t talk about demons. We don’t talk about land spirits, or curses, or elementals.

We talk about ghosts, a little. Mostly on TV shows. As teenagers we drive haunted country roads for a thrill. The adventurous among us book creaky downtown hotels out West and wait for the lightbulbs to shudder. I suspect the idea that something human died and didn’t finish crossing makes more intuitive sense—is slightly more hinged to our reality—than the idea that things that were never human share space with us every day, and shape our lives.

The problem is: What we don’t culturally believe in exists regardless of our belief.

If you don’t know that it’s possible to hike across a piece of land and run crosswise of a curse, you likely won’t sense when it’s happening and back off, or get cleared afterward. If you don’t know that it’s possible to move into a house with something that takes pleasure in your suffering, you’ll fall right into it. You’ll blame yourself, wonder if you need a new diagnosis. You’ll think you’re Garden Variety “going crazy.”

Both of these—the land curse, the entity—can have long-term consequences.

But data points that exist on different planes rarely get connected.

There’s an energy I start to feel south of Alamosa and Durango. It’s a change in the texture of the air, a slight shift in color. But it’s deeper than that too.

In college, I wrote my senior sociology thesis on something called “sense of place”—a popular academic translation of the Latin phrase genius loci, which more directly meant “gods of place.” Sense of place, in the sociological literature, referred to

“the meaningful relationship between people and places, encompassing physical setting, human experience, and interpretation… a deep bond relating to dependency upon place, rootedness in place, knowledge of place, and identification with place.”

Or that’s how I summarized it in my 80-page paper. What I knew then was a certain part of Wyoming had reached up into my body and gripped my heart with a fist—but that couldn’t be the work of an actual god, could it?

It could and it was. I wrote that thesis in the voice of sociology—emphasizing the systems and material realities that created human experiences of place—but even then I knew what obsessed me was deeper and more magical than that.

A land god is not the sum of its parts. A land god is distinct: not the cliff itself, nor the forests, but a spirit beneath them, both inhabiting them and more than them, old and capable of being angered. A land god cannot be diminished to an “attachment to place” or a “land use value.”

In so many instances, a land god decides who stays and who goes.

The land spirits do not obey the carefully-drawn lines of settlers. Nor do the curses drawn up by the Pueblo tribes, the Navajo, or the Hispaños who have been on the land for hundreds of years—especially in the places they were cornered, killed, nudged out of their homes.

Even if it bleeds past state lines, there is a particular energy I’ve come to associate with New Mexico. The wink of a trickster. A shimmer undergirded by darkness. The beckoning hand with a promise you know you shouldn’t trust, but can’t resist.

New Mexico’s nickname is Land of Enchantment.

I know, because I was enchanted.

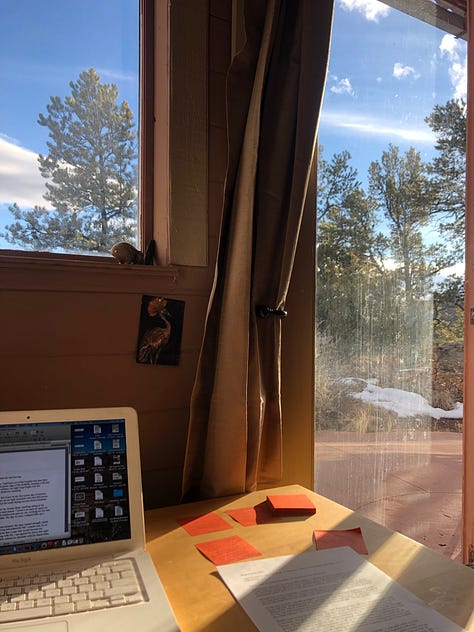

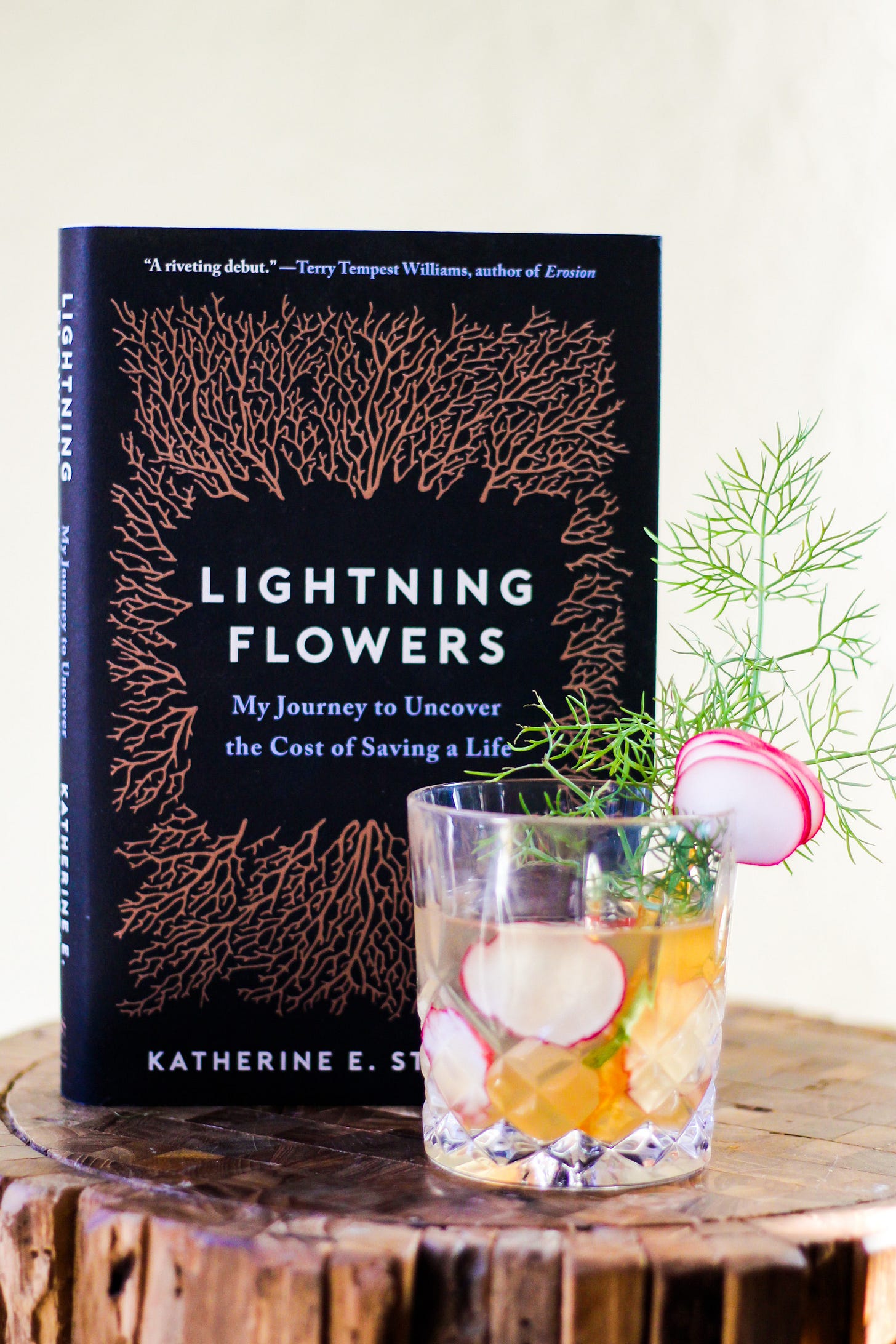

In 2019, I spent ten weeks on Glorieta Mesa while on deadline for my book Lightning Flowers. I’d sublet my house in Tucson to save on rent, living at writing residencies all fall—but then didn’t get into any for spring.

Something in my gut told me: Open AirBnB. Type in your dates and New Mexico.

The Earth Home came up first. A molded passive solar adobe with giant rainwater barrels, located in a forest of piñon and juniper, at the southern end of Glorieta Mesa. It was adorable, remote enough to keep me from distraction, and had its own temple carved into the rocks. I put it on my credit card.

The months I spent there—writing through blizzards, screaming through the most traumatic scenes of my book, and walking the dirt road beneath dizzying stars—are their own story. Maybe even a love song. When I returned home to Tucson in April, my house felt weirdly hollow. I missed tending fire. Longed for green chile cheese fries. Craved the stones that had felt so ancient. My phone kept suggesting I drive back to the “Significant Location,” 527 miles away, where I had just spent most of three months.

I wasn’t surprised when my Tucson landlord told me to move out so he could sell.

But first I tried to move back to Wyoming—where I’d always intended to end up. I couldn’t find a place. After six months (and too many guest rooms and AirBnBs and hotel rooms), I started touring Tucson houses again. I signed a lease, but on move-in day found the place filthy and full of a dead man’s stuff. (Three ghosts there, all angry.)

I broke the lease. I went back to New Mexico. I rented an adobe in Velarde, a backyard guesthouse off Santa Fe’s Agua Fria Street, an apartment above a rock shop in the Railyard. I began deep study with a qigong teacher, wandering the neighborhoods after class breathing in piñon smoke. A deep calm filled me. In Taos, I slept on a goji berry farm, in the cabin where Aldous Huxley wrote Ends and Means. I extended my stay, then again.

At some point, checking the Santa Fe Craigslist became a daily habit.

On February 11, 2020, I wrote the following list in my journal:

The house I am looking for is 20 minutes outside Santa Fe, with two bedrooms and possibly a little writing porch or other extra weird room. It’s adobe or wood. The floor is wood or tile. The light is beautiful. There are coniferous trees for year-round color, and also a few gorgeous trees that sing the seasons. The range is gas. The stove is wood, or there is a beautiful functional fireplace. The river is not far. There is a good, warm sun. It feels instantly like home…

In a little clearing, I split wood. The hills are visible from where I sit and watch the weather move across them. The kitchen is cheery, quirky and colorful in the right kind of way. The house is not my partner, but we exist in the right kind of conversation with each other. A pinkish brown is involved. So too a turquoise. There’s some kind of sweet screened door, to allow the sound of the birds when it’s nice out. There’s some kind of porch/patio. It’s easy. It is dear. A good trail is not too far. I wake quietly and look at the light.

When the house in Cañoncito came up on Craigslist—a place at the base of Glorieta Mesa whose turnoff I’d passed over and over driving up to the Earth Home—I saw everything I wanted.

My body bent towards the yes that scared me.

During my Tucson home tours, I had made a practice of asking the trees in the yard (or cacti, if there were no trees) whether or not I should move in. “No,” they told me. Even if it took me a moment to deduce a logical reason for their answer—a scam? a dickish landlord?—ultimately what they said felt inviolable. The trees were a voice I trusted even beyond my own.

And so during my virtual tour of the house on the Mesa, I stared past the landlord’s smiling talking face, to connect with a pine tree behind her.

“Am I welcome here?” I asked. “Should I move there?”

The answer, a resounding yes. I signed the lease sight unseen. I drove one long afternoon and half of a night back into the heart of New Mexico.

Much later, I would understand that a forest is not the same as a house. I would understand that a forest can view you eagerly, joyfully. A forest can be lonely. A forest might already love you, especially if you have the connection to trees I do.

A forest might try to keep you safe.

But in the end, a forest cannot help you with what is in the house.

People call New Mexico The Land of Entrapment. It’s a joke about how many of us visit and then don’t, won’t, can’t leave.

I have to say here: Your relationship to New Mexico can be different than mine. The glow might remain: a gold that fills you. There are people who move there and find their life. The land accepts and blesses them.

For me, the nickname rings darker. New Mexico is the place my sovereignty became a glimmering mirage. Where the choices I thought were mine twisted like a funhouse mirror. Where I found myself living into a nightmare, only I thought the nightmare was me.

New Mexico is the place I loved desperately even as it almost killed me. The place I almost couldn’t leave.

I passed through the gate just after midnight on February 29, a day that only exists liminally.

I had passed through a portal.

One January night a year later, I went for a walk in the absolute darkness. The forest smelled fresh and cold, frozen mud with a hint of piñon smoke.

As I passed through the gate, I thought—happily, looking up at the stars—how this was the time of year I’d first driven up Ojo de la Vaca Road. How it had been two years since I unexpectedly found my life there.

And it’s been two years since I laid claim to you, a voice said.

I smiled. Honored—I thought—by the gods of the land.

I had no idea what had claimed me.

With love—

NEWS & OFFERINGS:

CAMPFIRE: Deep Prompt Writing in Community

7/27 from 4:30pm-6:30pm MT and 8/28 from 7:00pm-9:00pm MT

It’s getting harder for many of us to write in this loud, loud world. Join us virtually for two hours to write to soulful, deep prompts inspired by spiritual texts. $40

Understanding the Spiritual Blocks in Your Writing Process

8/17 from 4:30pm-6:00pm MT (This lecture is free to paid Substack subscribers).

How do negative energies, ancestral curses, soul loss, dead family members, and other spiritual phenomena impact what’s possible in your writing process? And how do spiritual problems overlap with physiological trauma? Join me for a lecture and Q&A at the intersection of shamanism and writing—and free yourself to move forward. $50

DM me to book a Tree Reading. $50-$150 Sliding Scale for up to 45 minutes.

I went down a Substack rabbit hole this quiet sunny day only to find you and this. I also have had a long relationship with places, states (have lived in 5 US states now) and homes (owned 3). My last one in Santa Fe, well let’s just say I could relate to your experience. It had many beings trapped in the land under the house and at times I would be overcome by their fear, which I was struggling to “get a handle on” in my own reality and life. I have lived in NM 3 times and now safely out of harms way, I can see how I have been dancing with some very nefarious yet alluring shadows which I now am healing in my own being. Thankfully I found someone in my community that had successfully encountered this before (after two unsuccessful attempts) and helped the beings move out and on so I was released and was able to sell the house. A lot of suffering in NM, as you sensed. I also encountered a woman who I would say was completely possessed, which I don’t say lightly, with really dark and dangerous energy up in Abiquiu who tried to attack me psychically and physically. 4 years of this sort of thing, I could write a book on it and I may. Grateful those hard years are behind me and no desire to return.

It’s rare and validating to see someone talk about something that I hate to say but is pretty common though to lesser degrees. So thank you. I have thoughts to write about my experiences though I don’t have any subscribers to lose, so there’s my upside.

Did you write more about your experience there?

I didn't want to say it at the time, but that house scared me when I came to walk the creek with you. Not the place, but the house. Quite specifically. I am sorry it sucked you in so traumatically, but not really surprised. And the way you tell the story is just breathtaking, yet so real. Hugs to you.